"Trauma is a fact of life, but it doesn't have to be a life sentence."

Peter Levine

Trauma and Transformation

- A Holotropic Perspective on Trauma

This is an exploration of Holotropic Breathwork as a therapeutic method to help individuals heal from trauma.

We describe the holotropic approach and perspectives to working with trauma, sources of trauma and the transformation that is possible, illustrated by an experience description.

Holotropic Breathwork as a therapeutic method

Holotropic Breathwork is a therapeutic method of self-exploration that combines various therapeutic and self-awareness elements: breathwork, body and emotional work, music, art therapy methods, group processes, and the concept from trauma therapy of a compassionate witness and the emphasis on creating a safe space for inner work. The method also connects to ancient traditions of utilizing expanded states of consciousness for healing, learning, and exploring the mysteries of life, which are still present in various wisdom traditions such as shamanistic cultures and mystical branches of different religions, as well as in the emerging field of psychedelic-assisted therapy in the West.

Psychiatrist and researcher Stanislav Grof, along with his wife Christina Grof, developed Holotropic Breathwork in the 1970s. Empirical studies have shown that the method can be beneficial in the treatment of trauma and addiction, as it allows the exploration of unconscious material often underlying traumatic and addictive symptoms. In studies, participants have reported improved self-awareness and emotional well-being, reduced anxiety, the release of deep emotional blocks, and mystical experiences, which have been found to have therapeutic effects. Therapeutically, it is often used alongside other methods (e.g., EMDR, psychotherapy, mindfulness), and we believe it is an excellent experiential support in therapeutic processes.

Many people seek healing experiences through other expanded states of consciousness, such as strong experiential methods or psychedelic substances. These can often be healing, but we occasionally hear about poorly facilitated sessions, where one of the common denominators is lack of safety and insufficient support from facilitators, either due to too few facilitators or lack of experience. Some have also found psychedelic experiences to be too intense and, compared to those, have felt that Holotropic Breathwork is much safer, as the intensity of the experience can be more easily self-regulated, and one can choose to step out of the experience if it becomes too overwhelming. The facilitator training in Holotropic Breathwork (Grof Transpersonal Training) is internationally recognized for its high quality and ethical standards, and the method serves as a worldwide gold standard of how expanded states of consciousness can be facilitated deeply and safely.

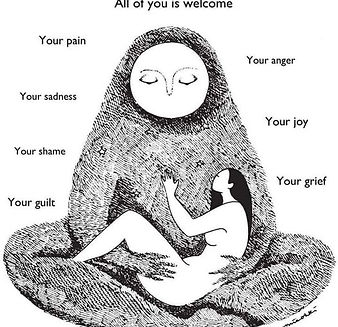

The concept of the inner healing wisdom

The content of Holotropic Breathwork sessions is always highly individual, but on a general level, it helps to strengthen the connection to the inner healing wisdom within each of us, guiding us towards wholeness, towards a fuller and more integrated life. The method is much broader than just trauma work, but for many, healing trauma is an essential part of their journey, guided by inner wisdom in a deeply supported and safe environment.

In a Holotropic session, when trauma rises to the surface, the strategy is to re-experience it with the presence of safety and support. Typically, in an expanded state of consciousness facilitated in a safe space, our window of tolerance grows significantly, and we are able to face difficult emotions, sensations, memories, or experiences that we might otherwise be unable to process or that could be (re)traumatizing without a safe space. In this way, people may experience highly intense emotions while simultaneously feeling safe. If the window of tolerance reaches its’ limit during a breathwork session, we do not push through but trust in the natural pace of the inner process. Emotional, psychological, and physical safety are the foundation of Holotropic Breathwork.

Trauma of omission

In omission trauma, a person has not received something necessary for a healthy development, such as basic security, food, a warm home, or more typically, nurturing care and touch. Especially in early childhood, and immediately after birth, the lack of human warmth and care can significantly affect the formation of the psyche, leading to various symptoms such as internalized insecurity, limiting beliefs, challenging ego states, or distorted identity structures resulting from developmental childhood trauma. Every person carries some degree of this kind of trauma.

When omission trauma surfaces in a Holotropic session, the creation of a safe and supported space may be enough to allow the internal wisdom to guide the breather through the experience. Often, the most healing experiences in vulnerable states come from another person's gentle and unconditional presence and touch, whether it’s holding hands, hugging, or being held. In Holotropic Breathwork, we facilitators do not fear touch—on the contrary, we have repeatedly seen how respectful holding, touching, or more active bodywork can be profoundly healing, providing an experience that cannot be achieved through talking or analyzing alone. At the end of this text, there is a powerful account of just such an experience.

Trauma of commission

In commission trauma, something has happened that exceeded a person's window of tolerance and boundaries. This could be emotional, physical, or sexual violence, a serious illness, a natural disaster, an accident, or witnessing a shocking event. Even physical injury or surgery can leave traumatic marks. When we experience a traumatic event that overwhelms our system's capacity to cope, one of the natural defense mechanisms of the body and psyche is to dissociate. In dissociation, part of us "escapes" to safety and detaches from our connected body-mind-soul. The charge caused by the traumatic event can’t then be naturally released but gets stored in the subconscious and body instead. In this stored state, trauma limits our ability to experience life in its full colors and can over time cause various psychosomatic symptoms, ranging from autoimmune diseases to diverse mental health challenges.

When commission trauma surfaces in a Holotropic context, the strategy is typically to experience the memory in all its intensity, but this time surrounded by safety and support, allowing the trauma to be released. Often, the safe space created in the session is sufficient, but an important aspect of Holotropic Breathwork is that the breather can ask for the support they need at any time, whether it’s the quiet presence of another person, gentle words, or physical contact.

Sources of trauma in the holotropic context

Stanislav Grof, the psychiatrist and researcher who developed Holotropic Breathwork, categorizes the experiences encountered in expanded states of consciousness—and therefore potential sources of trauma—into three categories.

Biographical experiences relate to the life we have lived so far. In a session, one might experience events and traumatic moments related to for example childhood or sexual history. Sometimes these come up as clear memories, sometimes more as bodily or emotional processes. The second category is birth and perinatal experiences, about which Grof has written extensively, particularly regarding the impact of birth trauma on the psyche. We facilitators also frequently encounter experiences that breathers link to their birth and time in the womb. These experiences can be quite dramatic, but processing them is often profoundly healing. The third category is transpersonal experiences, which transcend the ego-defined personality. This category includes healing intergenerational, collective, or karmic traumas.

Transformation

In a Holotropic session, we do not pre-determine what kind of experiences we will have; the important thing is to trust the guidance of the inner healing wisdom. This strategy of empowerment and trust in inner wisdom is a crucial part of the method's beauty and depth—in the session, we do not need an external expert to tell us what and how we should experience; we find that wisdom spontaneously within ourselves. It may be that you want to heal your trauma, and that kind of experience rises to the surface. But often, inner wisdom works in surprising ways. For example, we repeatedly hear from breathers that they expected a difficult, challenging breathwork session, but the content was something entirely different—light, blissful, and grounding. In every case, the session has been exactly what the breather needed in that moment.

A beautiful and merciful aspect of the method is that we don’t need to know what and how to experience. We can trust that our inner healing wisdom will bring to our consciousness those things that are most important for us to face and embrace at that moment.

"To heal is to touch with love what was previously touched with fear."

Peter Levine

Experience Description:

"The session began with anxiety and pain mixed with body tremors, which cramped and stiffened muscle groups one by one, moving from one part of the body to another. I tried to massage the pain away with my own hands, almost furiously. The cycle of trembling, pain, and desperate 'self-treatment' repeated—I don't even know for how long—but loud music was blasting in the background, and my frustration grew. Why can't the pain and anxiety just leave me alone? How long will this hell last?

The situation escalated when the pain and anxiety settled in my neck. Suddenly, I felt my hands grabbing my throat, and, as if possessed by some demon, they tried to strangle me. Panicking, I tried to sit up. Someone came to me, pried my hands off my neck, and guided me back down to the mattress.

Then, a heartbreaking, body-shaking wave of anxiety and anguish broke free in the form of tears and sobbing. 'I really wanted to be gone,' I muttered through my tears as I curled into the arms of the person helping me. I cried out my pain and sorrow deeply and for a long time. I was held, I was safe, cradled in caring and tender arms. At some point, my strength faded, the tears and sobs dried up, and I drifted into a space between sleep and unconsciousness. I was held—I was still safe. At the end of the session, when I woke up, I felt fragile and thin, as if I had been run over by a steamroller. My neck still hurting.

Mandala after the breathwork session.

Now, more than five years later as I look back at that experience, I still recognize it as the most terrifying and beautiful moment of my life: I physically faced all the despair, horror, and anguish that had once made me think there was no other way out but to end my life. At a time when suicidal thoughts lurked at the edges of my daily consciousness, I lived dissociated—head disconnected from body, thoughts separated from feelings. When those forbidden emotions and sensations arose in that breathwork session, I really felt them in my body for the first time. It was, at the very least, horrifying and intense. The beautiful and most significant difference was that, in the session, I was not alone—I experienced support and safety in my distress, and even in my desperate state, I was worthy of unconditional closeness and comfort. These were experiences that had been glaringly absent in my life when I sat on the cold tiled bathroom floor, toying with a razor blade against my wrist.

That session, as a healing experience, changed my life. Confronting my suicidal impulses in a supported and safe space has since allowed many other healing processes to begin: I was able to start learning self-forgiveness, which has been followed by genuine self-acceptance, recognizing and respecting my own needs and boundaries, releasing the fear that had chained my joy for life, gradually freeing my body, movement, and voice, and learning to care for—and even love—myself. The journey has been remarkable, and I am immensely grateful for every step along the way!"

Woman, 40